Customer discovery#

“If I had an hour to solve a problem and my life depended on the solution, I would spend the first fifty-five minutes determining the proper question to ask, for once I know the proper question, I could solve the problem in less than five minutes.” – Albert Einstein

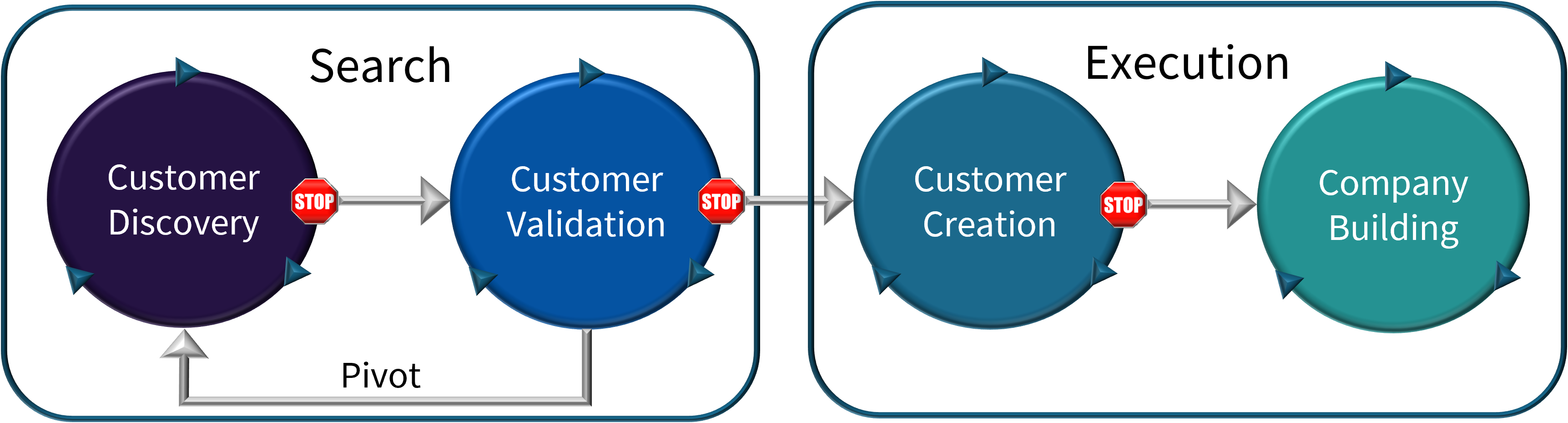

Recall the process for customer development process:

Fig. 10 alt: “The customer development process from chapter 1”#

Innovation takes us from thinking about clients and users to thinking about customers.

For this, we need to discover who are customers are and what they need. This is step 1 in the customer development process.

Customer discovery doesn’t mean that we literally need to find the exact people who will buy or use our product. It means something different.

But first, let’s define what customer discovery does NOT mean:

It does not mean that we need to understand the needs and wants of everybody, or even all of our customers.

It does not mean that we need to find every problem they have.

It does not mean requirements engineering.

It does not mean that we need to collect feature lists from customers.

It does not mean that we are running lots of focus groups.

It does not mean defining a product that we think is a good idea and trying to sell it.

Definition — Customer discovery

Customer discovery is the process of turning an initial idea or vision about a market or customers into a set of facts. The process tests whether the business model for a company solves real customer problems and whether the product features fit those customer problems.

When we think about building a product, we have an initial guess, called hypotheses, about people’s problems and how we can solve them. This is best considered a vision rather than a specific product. We fail when we assume that our guesses are facts.

Note

As a side note, I dislike the word “facts” in this context, because even once we go out and find customers to confirm our hypotheses, they are not certain. However, we’ll use the term “facts” to be consistent with the startup community.

The goal of customer discovery is to find out who our customers are and whether the problem we are solving is important to them. It emphasises discovery and iteration.

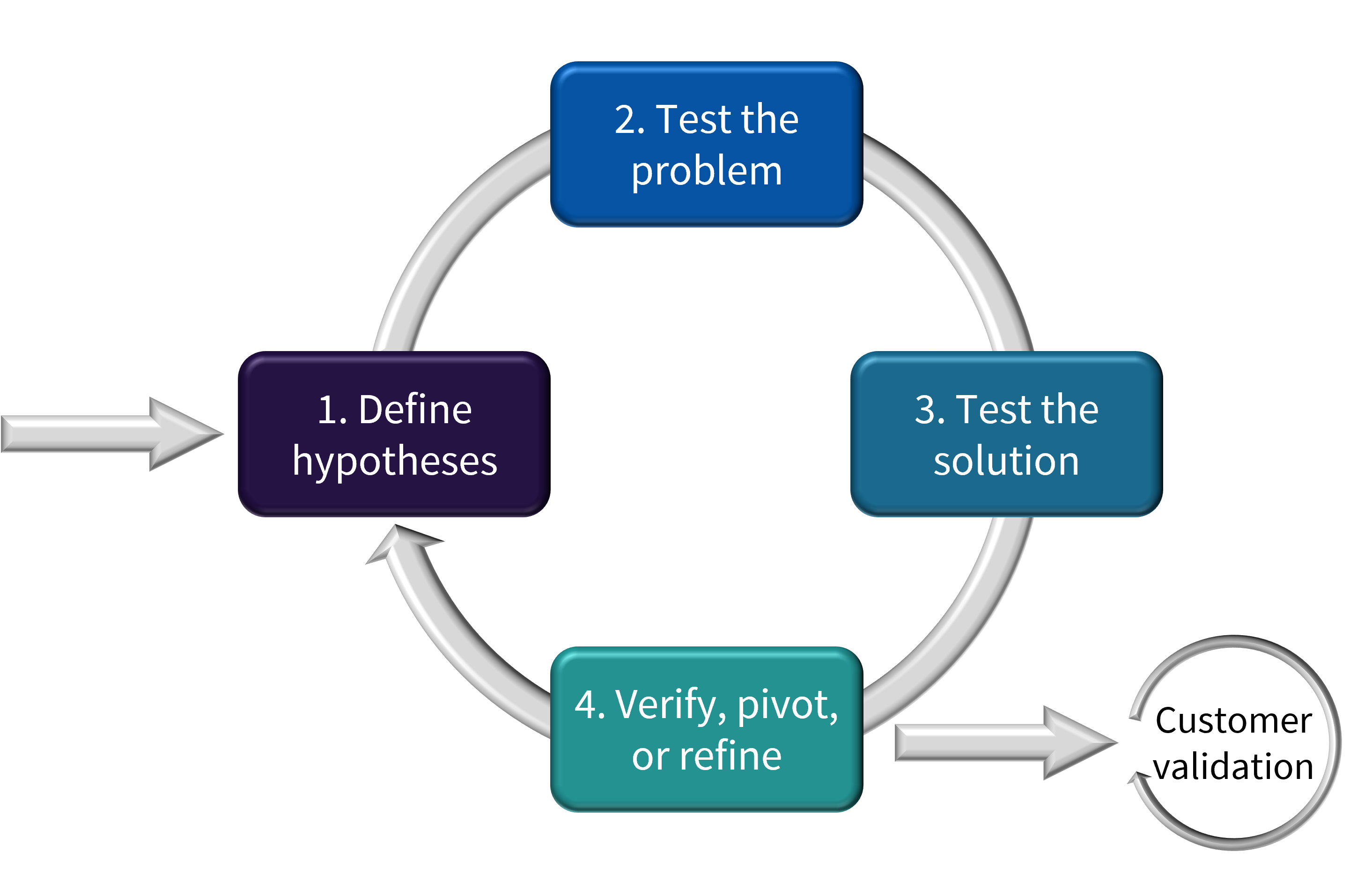

The customer discovery process, outlined in Fig. 11, consists of four phases:

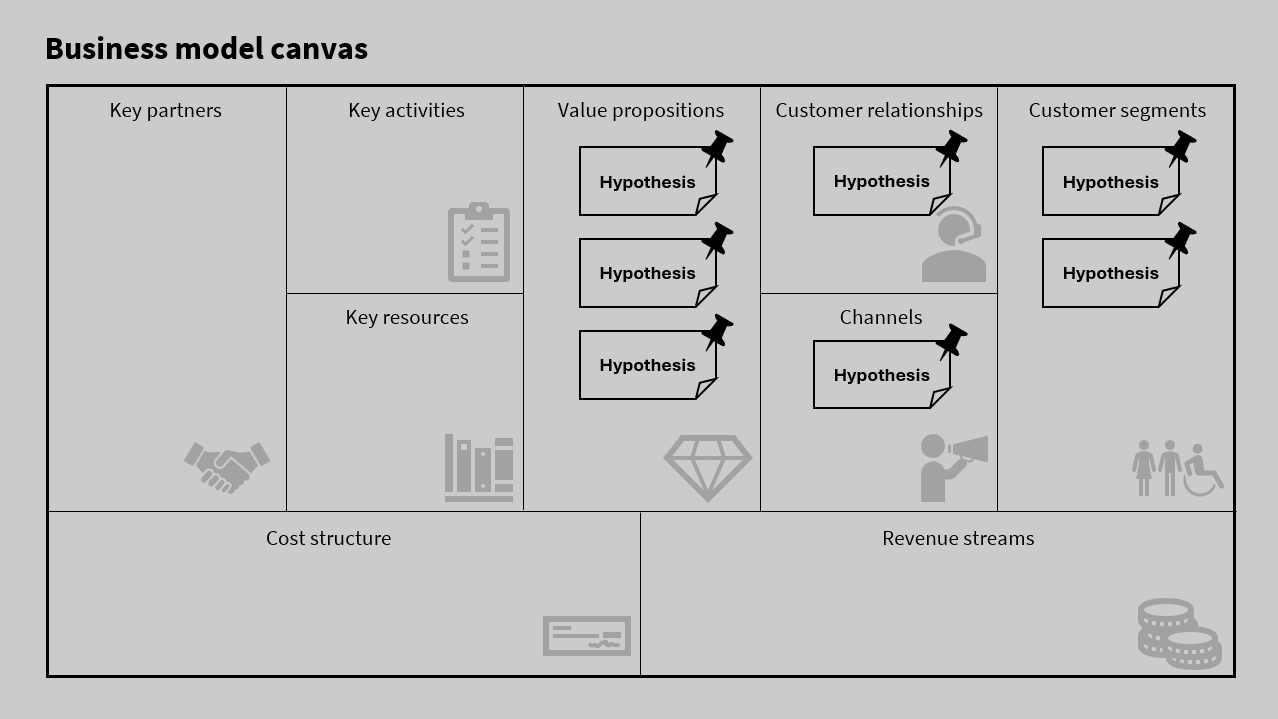

Define hypotheses: State our guesses and assumptions as verifiable hypotheses (more on this later) and adding these on a business model canvas (also more on this later).

Test the problem: Get out and speak to our customers to see if we have understood their problem. If not, return to step 1.

Create and test the solution: Get out and speak to our customers to see if our solution solves their problem and find out whether they would be willing to use it and pay for it.

Verify, pivot, or refine: For those hypotheses that hold, turn them into facts. For those that don’t, pivot or refine.

Fig. 11 The customer discovery process#

Typically, we want to be able to through this loop as quickly as possible, so that if we get some ideas wrong, we fail early.

Define our hypotheses#

To define our hypotheses, we first have to sketch our vision.

This means writing out answers to the following questions:

What are our customers top problems?

Does our idea help to solve these problems?

What would a day in the life of a customer look like before and after our product?

At this point, the answers to these are guesses or assumptions. We typically do not know if the answers are true. It may be “obvious” that they are, but many projects fail because team members don’t test “obvious” assumptions that turn out to be false.

This version really needs to just be a sketch. At this point, we shouldn’t be define detailed solutions to the problem, as we may be wasting valuable time designing a solution to a problem that doesn’t exist.

Like this…. |

… not like this |

|

|

At this point, we should be able to fill out a business model canvas with a set of hypotheses:

Fig. 12 alt: “A business model canvas with a some post-it notes specifying hypotheses in the value propositions, customer relationships, channels, and customer segments.”#

Of course, it may be that we already know the answers to some of these questions, either because there are other products that have demonstrated this – products from other organisations or even our own – or because someone has already collected the data for us. For example, Sony would have had an unverified hypothesis in the 1980s that people would like to have a portable music system with headphones to listen to music as they walked around. Once they sold millions of these, this hypothesis was confirmed for other organisations as well, who built on the idea.

However, there must be some questions we don’t have verified answers to. If we did already, it is because someone has already validated these by building the product, and we are therefore not really innovating at all. There is presumably something that we plan to do differently to competitors or to improve on earlier versions of our product, and those are based on customer problems that are usually not verified (yet).

Note

Customer vs. user

Note that we need to think broadly when we say “customer”. Importantly, we need to consider both our users and our customers — these two segments may be different. The users of a product are the people who will use it as part of their job, their life, etc. The customers are the people who pay for it. Consider the example of a person working in sales support, who would use sale support software, vs. the people who approve the purchase of this software, which may include the chief technology officer (CTO) or IT manager, the chief executive officer (CEO), or the chief financial officer (CFO); and maybe all of the above. We may need to talk to both the end users and the paying customers as part of customer discovery. We need to verify whether the end users really feel the pain of the problem we have identified; and also whether the CTO would be willing to pay for our solution.

We will use the term “customers” to refer to both end users and the paying customers.

Example – Medical alert system initial hypotheses

In our medical alert system example, we had some initial hypotheses that helped to defined out vision:

Older people want to be safe.

Families of older people want to know, on a daily basis, that their older family member is safe.

Older people want to be able to initiate a call for help and cancel any call for help.

Older people want to maintain their independence/autonomy.

Older people want to be cared for.

Older people do not want to have to press the green button each day to let the care company know that they are alive.

Older people do not to wear a visible (and ugly!) emergency alarm around their neck or wrist.

These are quite high-level for a product vision. At this stage, we had many ideas for potentially products, but these were not our focus just yet – we first wanted to go out and test our hypotheses that the issues our team member and his mother were having were widespread.

Test the problem#

Next, we need to get some data to test whether our customers really do have the problem we think they do.

To test these, we use experimentation, which we discuss further in Experimentation: Testing and validation.

Effectively though, we gather data that can be used to confirm whether our guesses/assumptions are correct or not.

Typically, this involves going out and speaking to potential customers about their problems. However, we may also be able to gather some data via other means, such as existing data sets. However, it is highly unusually to be able to verify more than a handful of hypotheses without talking to potential customers.

If the data we gather refutes our guesses, we need to re-visit our hypotheses.

If the data we gather supports our guesses, move to the next step.

Test the solution#

Next, we need to get some data to evaluate whether our solution really does solve the problem.

We test the hypotheses using the same process: going out to interact with customers.

What we take to these meetings depends on how much information we already have, how solid our idea is, and how easy it is to generate some material (e.g. a prototype) to gain feedback.

Verify, pivot, or refine#

At this point in the process, we should have a set of hypotheses that are either support (they become facts) or refuted:

Fig. 13 alt: “A business model canvas with a some post-it notes showing some refuted hypotheses and some facts in the value propositions, customer relationships, channels, and customer segments.”#

Similar to our initial questions, we end the customer discovery process when we have facts that answer ‘yes’ the following questions:

Do we know our customers top problems?

Do they recognise that they have this problem?

If there was a solution, would they buy it?

Can we build a solution at a price that they would pay for it?

If we answer ‘no’ to answer of these, we need to pivot or refine:

Pivot: Change our strategy and repeat the cycle of customer discovery again.

Refine: Change our product and repeat the cycle of customer discovery again.

Note

Be careful to distinguish between an individual customer not recognising that they have a problem (which would, in fact, mean they are probably not really a customer), and an entire segment of the market not recognising that they have a problem. If an individual customer does not see a problem, we move on to the next person (and maybe return to this customer later once early adopters are using our solution). If an entire market segment does not see a problem, we need to refine or pivot: either find a new market segment who does have this problem, or work towards a different problem.

Once we have a set of facts describing our customers and solutions to their problems that are verified, we can move on to the customer validation step.

What is a verifiable hypothesis? We discuss this in the chapter on Experimentation: Testing and validation.

Example — Medical alert system refined hypotheses

In our medical alert example, after some interviews with various stakeholders, we were able to verify:

Older people want to be safe.

Families of older people want to know, on a daily basis, that their older family member was safe.

Older people want to be able to initiate a call for help and cancel any call for help.

Older people want to maintain their independence/autonomy.

Older people do not want to have to press the green button each day to let the care company know that they are alive.

In the interview, hypothesis 5 was refuted:

Older people want to be cared for.

We found that older people wanted to be cared about, and otherwise rejected the idea that family and service providers should care for their safety, which is somewhat in conflict with the goal of being independent. Thus, we replace this with:

Older people want to be cared about.

We also partially refuted hypothesis 7:

Older people do not to wear an emergency alarm around their neck or wrist.

We discovered that:

Some older people wouldn’t mind wearing a wireless transmitter if it was not visible to others.

We also discovered some new hypotheses:

Older people wanted to be in touch with their family members, rather than a service provider.

Older people would prefer a medical alert that allowed them to be mobile (the alarms were attached to a phone line and the wireless transmitters have a short range).

Customer adoption patterns#

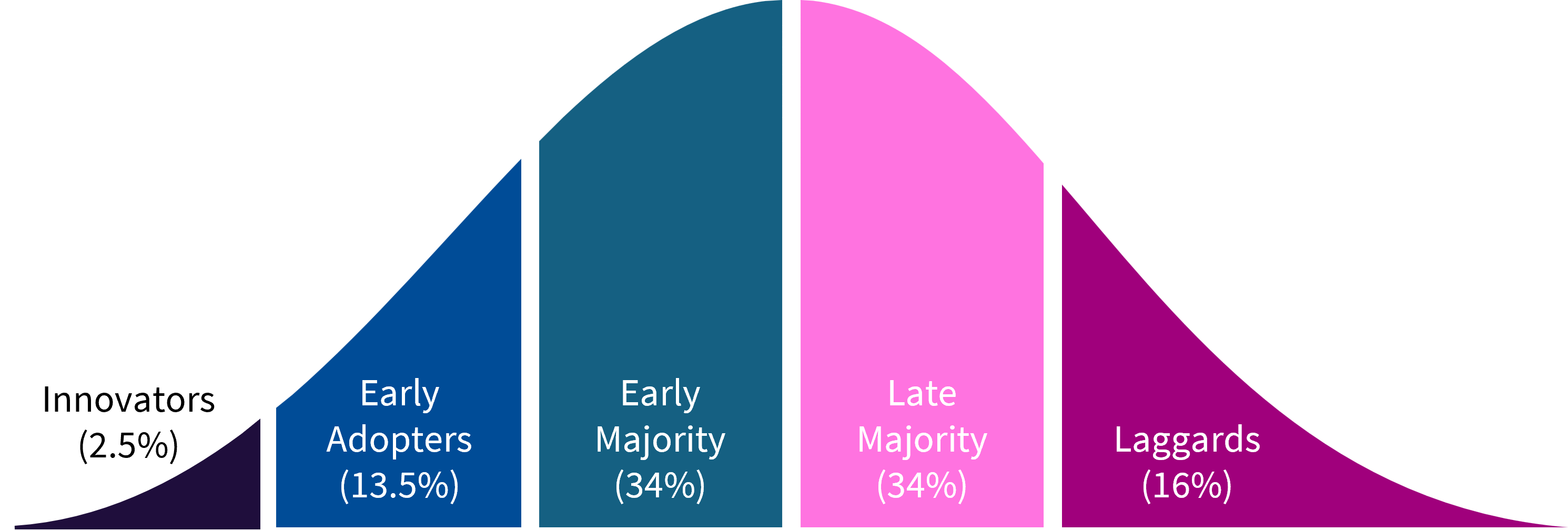

Fig. 14 Customer adoption patterns#

Fig. 14 shows the rough pattern by which customers tend to adopt new products. We have five broad types of customer in this pattern:

The innovators themselves who create new product, which make up a small amount of the market.

The early adopters, who typically adopt new solutions before others.

The early majority, who adopt once they see some people using a solution successfully.

The late majority, who adopt once they see many other people using a solution successfully.

The laggards, who typically don’t adopt or adopt very late.

Definition — Early adopter

Early adopters are people who typically adopt new solutions before others. They understand that they have a problem, want a solution, usually have an interim solution, and have the funds to purchase a solution. Often, they like to be on the cutting edge.

It’s important in innovation to initially focus on early adopters. Our goal in customer discovery is not to understand the needs of all of our customers. Instead, we want to develop our product incrementally: at first, just for the few early adopters, and once we have some paying customers, broaden to the early majority.

What makes early adopters so crucial? There are a few things:

They have a problem.

They know they have that problem.

They typically have an interim solution for that problem, or are actively searching for a solution.

They are willing and able to pay for a solution.

They tend to adopt things before others; while the rest of the market waits to see.

They tend to spread the word about your product if it works for them.

So, early adopters are “easier” to sell to, and help us to establish ourselves in the market. As such, focus on their needs first, and iteratively build a product that reaches the rest of the market.

In our medical alert project, many of our initial interviews were with people who were existing customers, and many of them (both older people and their families) told us stories to indicate that they thought there was sufficient room for improvement in these systems.

Customer development heuristics#

There are a few good heuristics to go by when doing customer development:

There are no facts inside your building, so get outside.

Develop for the few, not the many.

Early adopters make your product…

… And they know more than you about the problem.

Focus groups are for big companies, not startups.

Surveys don’t give insight compared to interviews — follow-up questions are difficult.

The goal for release 1 is the minimum feature set for early adopters.

Takeaways#

Takeaways

Customer discovery is a process for setting out a vision based on some hypotheses, and turning (some of) those hypotheses into facts.

It requires us to get out of the building and work with potential customer segments.

It is an iterative process.

At the end of each iteration, we decide whether we can continue to customer customer validation, or whether the need to pivot or refine.

Early adopters will be our first customers, so focusing on them can be valuable.