Value proposition canvas#

Definition — Value model canvas

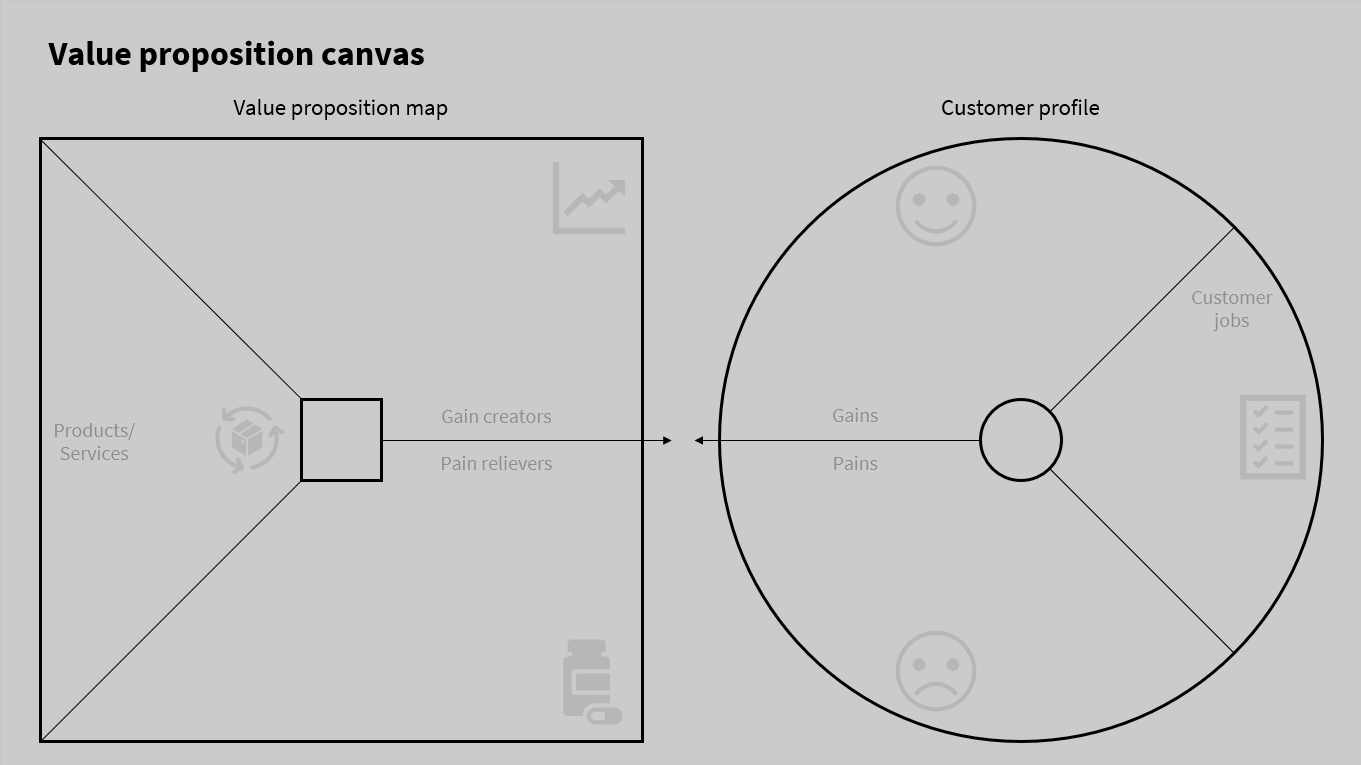

A value proposition canvas is a visual description of our customer segments, and our value propositions to solve the customers’ problems.

Fig. 15 The structure of a value proposition canvas. Source: reproduced from https://www.strategyzer.com/#

Fig. 15 shows the structure of a value proposition model. It contains two parts:

A customer profile, which describes the customers within a single segment, including their problems.

A value map, which describes the value propositions that potential solutions bring to that segment.

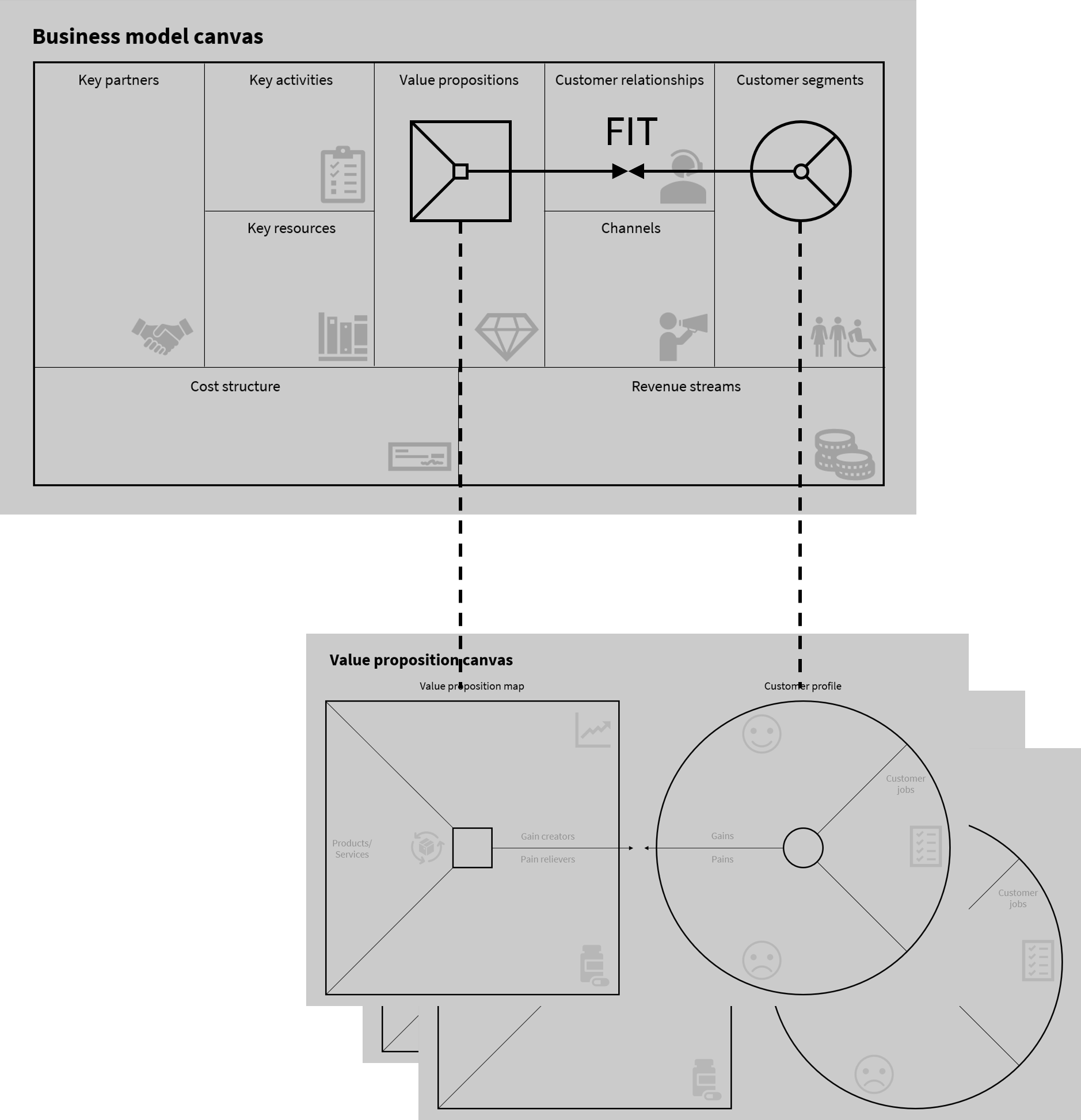

Value proposition canvases are used to define the value propositions and customer segments of a business model canvas. Effectively, for every segment, we map the segment to the value propositions that solve that segment’s programs. Therefore, there can be multiple value proposition canvases in a single business model:

The four types of startup markets#

When we are starting up a new product or company, there a four broad types markets:

Entering an existing market: The market is well-established and we are simply providing something with a different slant.

Creating an entirely new market: There is currently no market and we are establishing it.

Re-segment an existing market as a low-cost provider: There is a well-established market, and we are providing a surface at a lower price than competitors.

Re-segment an existing market as a niche player: There is a well-established market, and we are appealing to a niche part of the market via e.g. higher quality.

The features of a product are driven by how well they satisfy a market: the product/market fit. Larger companies tend to be market-driven, while startups tend to be product-driven.

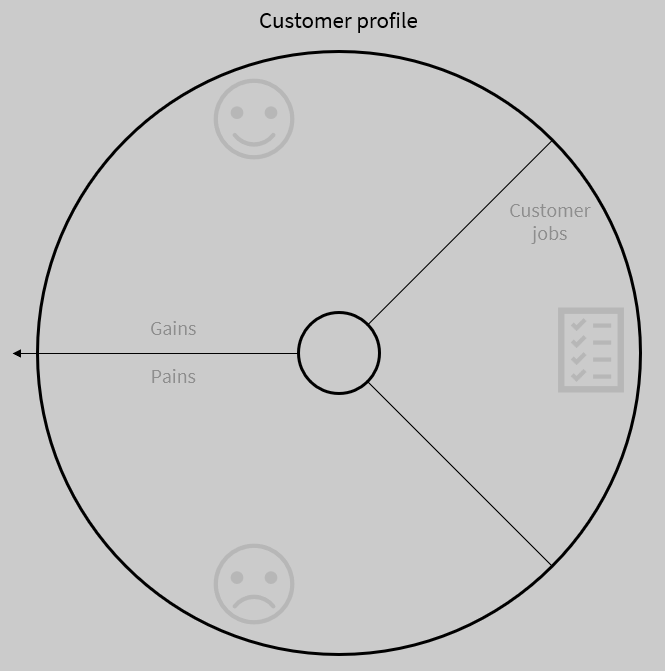

Customer profile#

Fig. 16 The structure of a customer profile. Source: reproduced from https://www.strategyzer.com/#

Customer jobs: Trigger questions[1]#

What is the one thing that your customer couldn’t live without accomplishing? What are the stepping stones that could help your customer achieve this key job?

What are the different contexts that your customers might be in? How do their activities and goals change depending on these different contexts?

What does your customer need to accomplish that involves interaction with others?

What tasks are your customers trying to perform in their work or personal life? What functional problems are your customers trying to solve?

Are there problems that you think customers have that they may not even be aware of?

What emotional needs are your customers trying to satisfy? What jobs, if completed, would give the user a sense of self-satisfaction?

How does your customer want to be perceived by others? What can your customer do to help themselves be perceived this way?

How does your customer want to feel? What does your customer need to do to feel this way?

Track your customer’s interaction with a product or service throughout its lifespan. What supporting jobs surface throughout this life cycle? Does the user switch roles throughout this process?

Customer pains: Trigger questions[1]#

How do your customers define too costly? Takes a lot of time, costs too much money, or requires substantial efforts?

What makes your customers feel bad? What are their frustrations, annoyances, or things that give them a headache?

How are current value propositions under-performing for your customers? Which features are they missing? Are there performance issues that annoy them or malfunctions they cite?

What are the main difficulties and challenges your customers encounter? Do they understand how things work, have difficulties getting certain things done, or resist particular jobs for specific reasons?

What negative social consequences do your customers encounter or fear? Are they afraid of a loss of face, power, trust, or status?

What risks do your customers fear? Are they afraid of financial, social, or technical risks, or are they asking themselves what could go wrong?

What’s keeping your customers awake at night? What are their big issues, concerns, and worries?

What common mistakes do your customers make? Are they using a solution the wrong way?

What barriers are keeping your customers from adopting a value proposition? Are there upfront investment costs, a steep learning curve, or other obstacles preventing adoption?

Customer gains: Trigger questions[1]#

Which savings would make your customers happy? Which savings in terms of time, money, and effort would they value?

What quality levels do they expect, and what would they wish for more or less of?

How do current value propositions delight your customers? Which specific features do they enjoy? What performance and quality do they expect?

What would make your customers’ jobs or lives easier? Could there be a flatter learning curve, more services, or lower costs of ownership?

What positive social consequences do your customers desire? What makes them look good? What increases their power or their status?

What are customers looking for most? Are they searching for good design, guarantees, specific or more features?

What do customers dream about? What do they aspire to achieve, or what would be a big relief to them?

How do your customers measure success and failure? How do they gauge performance or cost?

What would increase your customers’ likelihood of adopting a value proposition? Do they desire lower cost, less investment, lower risk, or better quality?

Prioritisation#

Once we have a list of jobs, pains and gains, we prioritise them:

Rank the jobs: what are the high-value jobs?

Rank the gains: what is the relevance of the gain?

Rank the pains: what is the significance of the pain?

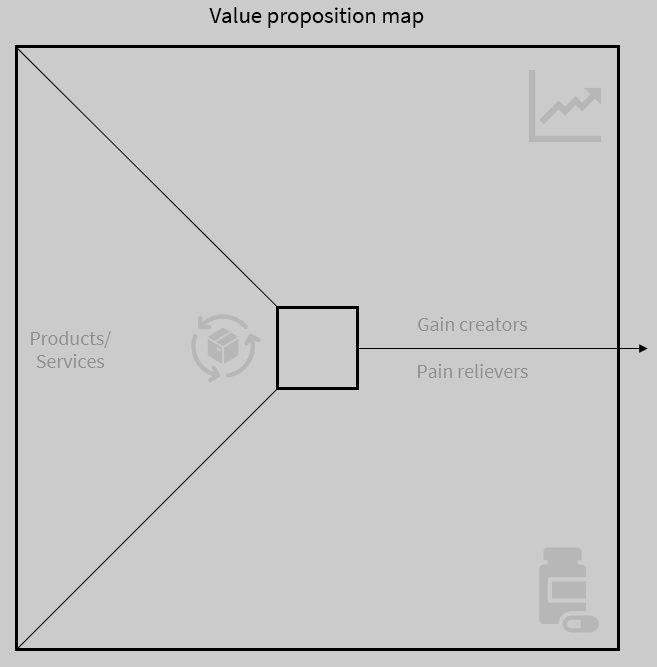

Value map#

Fig. 17 The structure of a value map. Source: https://www.strategyzer.com/#

Pain relievers: Trigger questions[1]#

Could your product:

produce savings? In terms of time, money, or efforts.

make your customers feel better? By killing frustrations, annoyances, and other things that give customers a headache.

fix under-performing solutions? By introducing new features, better performance, or enhanced quality.

put an end to difficulties and challenges your customers encounter? By making things easier or eliminating obstacles.

wipe out negative social consequences your customers encounter or fear? In terms of loss of face or lost power, trust, or status.

eliminate risks your customers fear? In terms of financial, social, technical risks, or things that could potentially go wrong.

help your customers better sleep at night? By addressing significant issues, diminishing concerns, or eliminating worries.

limit or eradicate common mistakes customers make? By helping them use a solution the right way.

eliminate barriers that are keeping your customer from adopting value propositions? Introducing lower or no upfront investment costs, a flatter learning curve, or eliminating other obstacles preventing adoption.

Gain Creators: Trigger Questions[1]#

Could your product:

create savings that please your customers? In terms of time, money, and effort.

produce outcomes your customers expect or that exceed their expectations? By offering quality levels, more of something, or less of something.

outperform current value propositions and delight your customers? Regarding specific features, performance, or quality.

make your customers’ work or life easier? Via better usability, accessibility, more services, or lower cost of ownership.

create positive social consequences? By making them look good or producing an increase in power or status.

do something specific that customers are looking for? In terms of good design, guarantees, or specific or more features.

fulfil a desire customers dream about? By helping them achieve their aspirations or getting relief from a hardship?

produce positive outcomes matching your customers’ success and failure criteria? In terms of better performance or lower cost

Six ways to innovate from a customer profile#

Alex Osterwalder outlines six ways to innovate from customer profiles[1]:

Strategy |

Explanation |

|---|---|

Address more jobs? |

Can we help customers complete more jobs in their day? |

More important jobs? |

Can we help customers do something more valuable? |

Beyond functional jobs? |

Can we help customers create value by fulfilling important social and emotional jobs? |

Help more customers? |

Can we help more customers by making jobs easier or cheaper? |

Do a job better? |

Can we help customers do a higher quality on existing jobs? |

Competitor Analyses#

Once we have a solid idea of our value proposition, we need to analyse our competitors.

Why is a competitor analysis important?#

There is no point trying to sell a product if we have a competitor who does it as good or better than us. A product is only successful if it offers a unique value proposition.

If you think: we don’t need a competitor analysis – we know our value proposition is unique, a clear response is: how do you know it is unique if you haven’t done a competitor analysis?! There are many “unique” apps on the Apple and Android app store that all do much the same thing.

Further, analysing how our competitors solve their customers’ problems can give us insight in two ways:

If they do something well, we can mimic it (provided it is not patented or copyrighted).

If they do something poorly, we can learn from this and try to do it better.

What is a competitor analysis?#

A competitor analysis is conceptually simple, but can be challenging to do.

It typically has the following parts, which correspond to the process that we can follow:

Define unique value proposition: Write a short, clear statement of what we believe our unique value proposition is.

Find competitors: Search for competitors who are solving the same problems.

Analysis: Complete a competitor table and a short Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats (SWOT) analysis the top few competitors.

Insights and strategy: Summarise what we learnt and how it changes our plans.

Define unique value proposition#

We should have already defined our value proposition by this point, but it helps to start a competitor analysis with a short, clear statement that specifies it:

Our project, [Project Name], aims to solve [brief problem statement] for [target customer segment]. We believe that our unique value proposition is [value proposition]. The following competitor analysis includes a comparison table, SWOT analysis of key competitors, and strategic insights based on our findings.

Find competitors#

Next, we need to find our closest competitors. There are two broad types of competitors:

Direct competitors: Offer the same type of solution to the same customer segment and their same problems. For example, someone offering a product that connects families via mobile devices is a direct competitor to the emergency alarm ‘picture frame’.

Indirect competitors: Offer a different type of solution to the same customer segment and their same problems. For example, existing emergency alarm companies offered a service rather than connecting families directly – same pain, very different solution.

How do we do find competitors?

Here are five ways:

Customer interviews: We can look at our customer interviews! If we did our job properly, we should have been probing how our customers currently solve their problems. This gives us insight to our competitors.

Search engines: We can run the types of queries we expect that our customers would run when trying to solve their problems.

Customer channels: Look at distribution channels, such as app stores or other product platforms. For physical products, we could look at online sellers or even go into stores.

Social media: Browse forums, etc., about your customers’ problems to see what products people currently use.

Industry trade shows, blogs, etc: Look for public forums about the specific industry, and do things like attend trade shows to learn about competitors.

Analysis#

Put together all of the competitors that we have analysed into a competitor table:

Competitor |

Direct/indirect |

Target Customers |

Key Features |

Pricing Model |

Strengths |

Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Competitor A |

Direct |

Small businesses |

Automation, dashboard |

Subscription |

Easy to use |

Limited integration |

Competitor B |

Direct |

Enterprises |

Custom workflows, analytics |

Tiered pricing |

Scalable |

Complex setup |

Competitor C |

Indirect |

Freelancers |

Simple UI, mobile app |

Freemium |

Affordable |

Few advanced features |

…. |

… |

… |

… |

… |

… |

Next, for the most closely related competitors, that is, those whose market share you are hoping to steal, do a SWOT analysis:

Strengths: What do they do well? What unique capabilities do they have?

Weaknesses: Where do they struggle? What are people’s complaints about their product?

Opportunities: In the market they are in, what are trends or gaps that they can benefit from?

Threats: In the market they are in, what challenges do they have? What is changing that could make them less valuable?

Strengths may similar similar to opportunities, and weaknesses to threats. The difference is:

Strengths and weaknesses focus on the properties of the organisation or product.

Threats and opportunities focus on the properties of the market they are in.

Example

Competitor A

Strengths: Intuitive interface, strong customer support.

Weaknesses: Limited scalability for larger teams.

Opportunities: Growing demand for lightweight tools.

Threats: New entrants with better integration capabilities.

Competitor B

Strengths: Robust feature set, enterprise-grade security.

Weaknesses: High learning curve.

Opportunities: Expansion into mid-market.

Threats: Price-sensitive customers switching to cheaper alternatives.

Tip

You should know your closest competitors so well that you should be able to fill out a business model canvas about their product(s)!

Insights and strategy#

Now that we understand our competitors, what can we learn from how they operate?

A nice way to think about this is:

What did we learn about our competitors?

What does that change about our own understanding or hypotheses?

Example – Insights and strategy

Insight |

Strategic implication |

|---|---|

Most competitors focus on scalability |

Can we focus on being niche and quality to differentiate ourselves? |

All charged more than we expect to |

Are we under-estimating the costs to do this? We need to test price more/better |

There is a gap in direct family-to-older-person communication |

We need to test the hypothesis that people want this |

Most competitors had a complicated sales and sign-up process |

We need to avoid over-complicating this. |

… |

… |

Takeaways#

Takeaways

A value proposition canvas describes our customers, their problems, and the value propositions to help with these problems.

It contains two parts: a customer profile and a value map.

A customer profile describes the jobs, gains, and pains of customers in a segment.

A value map describes the pain relievers, gain creators, and products/services behind these.

When we interview customers to construct profiles, we need to listen.

Interviews aren’t about just asking questions – they are about learning.

We analyse competitors both to find unique value propositions, and to learn.